A Delaware Water Gap National Park?

Evaluating the Redesignation Controversy

By Jim Alexander, updated October 18, 2022 and October 25, 2024.

The Setting | The Park Proposal | The Opposition |

Comparability Argument | National Parks Generally |

Happening at the Water Gap | Lesson from the Past for the Future

The Setting

“Recreation, more than any other feature of the Tocks Island Project, was used to sell the project to the public.” So observed Richard C. Albert in his 1987 Damming the Delaware, a comprehensive overview of the entire Tocks Island effort.[1]

The idea of creating the Delaware Water Gap National Gap Recreation Area was added to the dam proposal when the required economic cost-benefit analysis for just the dam and reservoir fell short of justifying the project, especially important in light of competition for federal dollars that were needed for the Vietnam war.

The recreation was originally envisioned as occurring on the reservoir and on the narrow strip of land on both sides — an area featuring farms, scattered residences, waterfalls, woods, mountainsides and magnificent expressions of nature.

And as it turned out, the resulting Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area was the only survivor of the failed project, and a magnificent thing it was, blocking commercial development of a splendid natural area which Albert referred to as A Central Park for Megalopolis. Along the way, communities were destroyed, people uprooted and lives disrupted.[2]

If one could accept that as a price for preserving 70,000 acres of river and nature, there still remains one critical failure: the lack of adequate Federal funding to maintain the Recreation Area.[3] The area turned out to be larger than anticipated because without the dam, no land aside from the river was under water. Year after year, decade after decade, the National Park Service struggles to maintain roads, provide parking and amenity services, maintain safety on the river and on the trails, and to cope with both the hundreds of thousands of visitors and the decay of historic structures. With so little funding, no matter what priorities it chooses are often seen as wrong or insensitive. And as the inheritor of the Corps of Engineers’ heavy-handed eminent domain procedures and related actions by some early Park Service personnel trying to implement Congressional policy, the Service continues to bear criticism, despite its best current efforts.

As time progressed, and Interstate 80 was built, visitor loads increased. The Park Service claims it is some 4 million a year, a figure which is sometimes criticized as too high,[4] given the nature of local residents traversing the area for non-park purposes and difficult measurement techniques. Surrounding areas did develop, but with the federal government not paying property taxes, local governments and volunteer organizations were heavily impacted by the need for support services, including emergency response on the roads and river.

In peak periods, parking lots and facilities are regularly overloaded and often closed. At times some visitor centers have been closed. In Winter, some roads are closed for lack of funds to keep them clear.

When a power line was authorized across the valley, the Service devoted a substantial portion of the associated remediation revenues to rejuvenating the natural Watergate area astride Van Campens Brook. While that was underway, historic buildings continued to collapse and fall prey to vandals, and the roads and parking areas continued to be overwhelmed. It was not unusual for visitor areas and parking lots to be closed because of lack of staff, space, and resources. This in turn generated criticism, despite the beneficial impact on the waterway.

In an effort to position itself for any funds that did break loose, the Service undertook a study and prioritization of historic structures. While its adoption has not officially happened, and it has not produced any new funds, the NPS anticipates relying on it as it does seek future available funding, including possibly for a future Great American Outdoors Act round. Complicating this is the distinction between buildings that are just old, but represented a way of life that some remember and cherish, and those that have intrinsic historic value, such as the first house built in Warren County, which stands along the Old Mine Road and is boarded up and periodically vandalized. Simple math indicates that the Service can’t adequately deal either with visitors or preserve history with its current level of funding; that leaves nobody happy.

Given the nature of its hillsides, waterways, trails and woods, the area can geographically absorb a substantial number of daily visitors, but they need places to park and support facilities, and there is little flexibility to accommodate and service current let alone more visitors.

Delaware River National Park and Lenape Preserve Proposal

So, what to do? A currently promoted idea is to change the National Recreation Area’s name!

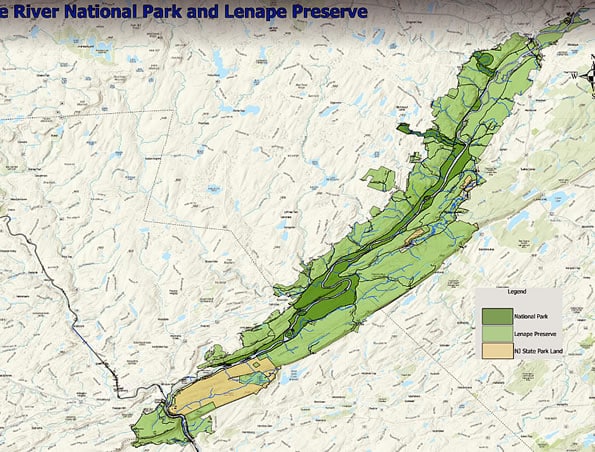

The Pennsylvania and New Jersey Sierra Club chapters (the NJ chapter subsequently withdrew their support), in concert with retired Water Gap Recreation Area superintendent John Donahue, are now pushing for a legal reconfiguration of the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area. It would be renamed the Delaware River National Park and Lenape Preserve.

Modeled after West Virginia’s New River Gorge National Park and Preserve, the proposed (same) site would consist of about 9,800 acres of National Park, and over 50,000 acres in a Lenape Preserve. Donahue, as the prime spokesman for the idea, asserts that the benefits will include:[6]

- Greater prestige for the site, because “National Park” is more impressive than “National Recreation Area.”

- Resulting expanded visitation, with visitors benefiting from greater opportunities to enjoy nature, and local businesses outside the park enjoying more people with their attendant needs for lodging, restaurants, gasoline, etc.

- The potential for receiving more Federal funding, allowing the Park Service to deal with the roads and other infrastructure problems.

- The Sierra Club also emphasizes increased potential value through the possible adding to the new site’s area if Pennsylvania and New Jersey were to donate existing State areas such as Worthington State Forest to the new national site, and possibly connecting up some smaller nearby parcels through voluntary acquisition.

- The ability to provide recognition to the original inhabitants of the Valley, the Lenape Indians, who were pushed away with the advent of European settlers. (The Dutch who had occupied the valley remained, but under English governance.)

The idea was first floated some years ago, in an NPS working document called “Vision 2030: A Vision For A Sustainable Future,” and dropped in the face of adamant opposition from hunters and others who frequent the area. Now, it is asserted, while the proposed smaller National Park portion could not allow hunting, the larger Lenape Preserve will. The Preserve would feature some unspecified Lenape cultural and educational center as well. The effort has created its own website at https://ourpark.org as seen above.

The Opposition

Local opposition to this proposal was quick to arise. Concerns coalesced under the leadership of Sandy Hull, a resident who had been forced to move just out of the park’s boundaries in the 1970s, when the dam project was being pushed, and who had at that time helped with the efforts of the Delaware Valley Conservation Association – the primary organization rallying the opposition against the dam. Since then, she has maintained a focus on developments in the area, including a particular concern over how the legacy of people who lived in the area has not been adequately pursued; in particular, the neglect of hundreds of homes and structures that were part of the pattern of life that the area’s acquisition disrupted.

Hull (r), a resident of Layton, NJ, was joined by Kristin Albrecht (l), an energetic resident of Milford, PA, who worked with her to create an opposition website at https://www.nonationalpark.org/ as well as helping with their Facebook Page https://www.facebook.com/groups/nonationalpark. An Instagram site[8] has also been created, which focuses on debunking claims made for the new designation. With the support of hundreds of other local and concerned citizens, they have undertaken an active program of visiting community and local governmental groups and lobbying against the proposal. The current official 501(c)3 organization is called the Delaware Water Gap Defense Fund.

The Facebook page has some 5,300 regular followers, with more joining. They have also established an online petition against the park idea, with some 7,600 signers so far.

Their main complaints are the lack of specificity of the proposal, and the likelihood of increased visitation overwhelming the surrounding area and especially the park itself, long before any increased revenues would come on stream, assuming that they ever did. In fact, they point out that there is no guarantee whatsoever that changing the name will bring in any additional Federal funds. Even Donahue admits that. They are further concerned over the impact of more people on the land and what it represents.

They also point out that major projects such as the multi-million-dollar rebuilding of Route 209 through the Recreation Area are being funded not as a result of being a park or not, but from the Great American Outdoors Act.

And one might ask: “if being a National Park really does draw more funds than a National Recreation Area, will the proposed smaller Park component’s ability to gain increased funding be matched by the much larger Preserve’s ability to be similarly funded? How would that really work? Specifics are not available, so we’re left to wonder.

While there are numerous complaints raised by the growing number of visitors to their Facebook page and elsewhere, underlying all is a lack of credibility regarding any touted benefits of the name change, based on the reality of decades of underfunding, not to mention a worry over change being foisted “from above.”

Take the proposal to designate a major part of the area as a Lenape Preserve, featuring some sort of Lenape cultural center. Critics suggest that it has the hallmarks of being more an effort to assuage the hunters than of a deep commitment to the original native inhabitants. In fact, the efforts to secure official Lenape backing have been directed to national Lenape organizations in the Midwest, while local New Jersey Lenape have felt ignored, and actually are not supportive.[9]

Some observers have suggested that it is an effort to gain support of the current National Park Service Director Charles F. Sams, a distinguished member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Northeast Oregon, as reflected in this visit to Washington by the proponents of the change:

This is indicative of a contradiction in the proponents’ approach. Donahue speaks of building understanding by meeting with local groups, but portions of the Sierra Club (the New Jersey chapter withdrew its support) seems more focused on obtaining approval in Washington. They even cite that the change could be accomplished, not by specific debated legislation, but as a provision slipped into some broader Congressional “must pass” legislation. In fact, that is how the original Tocks Island dam legislation was enacted.

Donahue adds that: “the park belongs to the people of Wyoming and New York City as much as it does to locals.”[11] He characterizes criticisms of his proposal as “misinformation, falsehoods and canard,” (see https://delawarecurrents.org/2024/10/05/delaware-river-national-park-3/) yet his proposal seems to morph from time to time in an attempt to gain support; he wages the campaign without direct dialog with opponents. Some local residents are puzzled as to the true motivation.

The Comparability Argument

All National Parks are not created equal. The “crown jewels” in the system that are often mentioned as an example of benefits that might accrue at the Water Gap are typically much larger. Grand Canyon, Yellowstone and Death Valley are in the 1-million-acre range.

And some have special circumstances. The New River Gorge National Park and Preserve, a recent addition, is about 72,000 acres, of which 7,000 are in the Park, and 65,000 in the Preserve, and might be thought of as comparable in size. It is cited by the proponents as what might happen at the Water Gap with a name change. But New River has one special thing going for it: a heritage of West Virginia’s senators wielding substantial influence in Congress, resulting in considerable Federal largess going its way. This is especially enhanced by the unique role of the current senior Senator, Joe Manchin. (Do note that New River Gorge reportedly received no additional funding simply because it became a national park, and as of 2021 park leadership reportedly was not sure if any extra money would be provided beyond its existing annual budget of $8.7m.)

Related to the funding question is a comment by a local government official in the affected West Virginia town, Melissa Dragan of Thurmond, WV, who told Hull “don’t let this happen to you.”[12] In New Jersey’s delegation, however, there is competing legislative interest in funding pressing urban and social needs. Parks, unlike people, do not vote.

A substantial number of local governments in both states have spoken out against the plan, either outright opposition or frustrated by the lack of specifics, and worried about being saddled by added burdens such as traffic, road congestion, police and fire services.[13] Some state legislators have spoken out against it. The respected Delaware Riverkeeper recently expressed opposition to the plan in cogent terms.

As of this writing, the Park Service itself has not taken any stand on the proposal, but regarding the question of whether designation as a National Park would bring added funds, has stated: “A park’s base funding is provided through regular appropriations and is determined by the number of visitors, mission-essential activities, number and historic designation of facilities, acreage, road and trail mileage if applicable, and other factors.”[14] In fact, within the NPS, a facility’s name does not affect its priority for fund allocations. Given that a name change would require Congressional action, and the proponents are seeking to achieve the change “from the top down,” this may place the Park Service officials in a difficult situation.

Currently, some visitor facilities remain closed, and some roads are closed off season because of the cost of keeping them open. To be sure, any increase in visitation will further stress the limited road, rest area, parking and recreational facilities, not to mention visitor guide and public safety services. The physical nature of the area, with long narrow strips of land, much of it sloped up to the mountains, actually does not always lend itself to new roads or facilities. And more people both inside and near the proposed park will require new water and sewer systems, with attendant pollution concerns. Nearby areas, already hit by development, warehouses, and traffic, will be under greater stress.

There exist funding questions regarding catching up, building new, and then maintaining the new, about which the current record is not at all encouraging. One keen observer of the current situation on the Old Mine Road[15] noted the presence of port-a-potties in front of a closed, relatively new rest room facility, wryly commenting:

“Why is it that Congress is able to appropriate millions for projects like Turtle Beach but when it’s time to fund the maintenance of these projects the money is no longer there … [those with] dreams of national park status … will look to these magical port-a-johns to provide sanitary solutions to the multitude of new visitors.”

What’s Happening to National Parks Generally

In considering the possibility of a National Park, it is helpful to consider what is happening nationally. One article published on cnbc.com a year ago discusses emerging problems of parks drawing more visitors than can be handled. A similar chilling picture of the impact of large numbers of visitors overwhelming nature can be viewed at “Crisis in our national parks: how tourists are loving nature to death.”[16]

These sources note that visits to Glacier and Yellowstone have doubled since 1980, and that overall, national park visitation was 20% higher in 2019 than in 2013. Some parks were requiring advance access reservations, leading to visitor consternation. One of the reviews concluded that “Backcountry trails are clogging up, mountain roads are thickening with traffic, picturesque vistas are morphing into selfie-taking scrums. And in the process, what is most loved about them risks being lost.” And “Recent research has found national parks bear the disproportionate brunt of global warming – and years of wear and tear have seen park maintenance fall woefully behind. The current backlog of necessary upgrades to roads, trails and buildings stands at more than $11bn.”

Senator Angus King of Maine, chair of the Senate Subcommittee of National Parks, was quoted as saying that there’s a tension and a paradox in this dynamic. On the one hand, it’s good that Americans are visiting public lands in record numbers. But overcrowding has led to more litter, vandalism and traffic – stressing parks’ natural resources and wildlife and negatively impacting visitor experiences. He told a Senate hearing “We can accidentally love our parks to death.”

Coupled with this is the fact that Federal and state parks, by whatever name, come into existence through separate pieces of legislation, occurring over many decades, and not as part of a broader plan, let alone one which adjusts for changing times.

At the time, an NPS representative pointed out that half of all recreation visits occur in the top 23 most visited parks, with “significant congestion” in most of them. For 2020, the Delaware Water Gap Recreation Area was listed as the eleventh on the list of most visited National Park Service sites.[17]

What’s Happening at the Water Gap

So if that’s the national picture, is the Delaware Water Gap National Gap Recreation Area similarly affected? The Area’s November 2020 National Park Service Visitor Use Management Plan,[18] 148 pages in length and professionally presented, in its Executive Summary says in part:

- The park is among the top 20 most-visited units of the national park system with an average of approximately 3.8 million visitors annually and is one of the largest parks in terms of infrastructure responsibilities. It is less than a 2-hour drive from New York City and from Philadelphia.

- Many of the visitor use issues stem from the growing popularity of the park, the increased demand from nearby urban areas, and the changing needs of park visitors.

- Some of these issues include the desire for visitors to access the water and associated recreation activities in spite of growing crowds, a lack of facilities commensurate with visitor needs and usage, and visitors recreating in areas that may be unauthorized, such as creating their own river campsites and recreational use sites. The park has also experienced increasing numbers of large groups visiting the park in areas currently not designed to accommodate this use, especially in areas with sensitive resources. This disparity between use types and facility design leads to a variety of issues including but not limited to visitor displacement and crowding, resource impacts, and visitor conflicts.

In describing the site, the report notes:

- The river and surrounding landscape support a wide variety of opportunities to enjoy the natural and cultural resources of the park during all four seasons. Another one of the park’s fundamental resources and values is sustainable access to high-quality recreation opportunities….

- Visitors to DEWA participate in a diversity of visitor experiences and high-quality outdoor recreational opportunities including boating, swimming, hiking, hunting, fishing, picnicking, biking, scenic driving, birdwatching, rock climbing, and cross-country skiing. In addition, the park offers more than 100 miles of official hiking trails, including nearly 27 miles of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail. The remoteness found in some areas of the park offers the chance to experience solitude, while other areas provide social recreational settings.

Clearly, there’s a lot going on in this relatively small area. So, what did the report find? Broadly speaking, they indicate a reasonable level of visitor satisfaction from their 2015 surveys, coupled with a series of concerning negatives which included:

- Parking areas inadequate to meet demand.

- Swimmers contending with anglers for use of streams, with some confrontations.

- Unlawful alcohol consumption, drug use, and bad behavior.

- Crowding.

- Visitors creating unauthorized campsites and trails.

- Trampling of vegetation and packing of the ground.

- Human waste and trash on the ground as a result of inadequate facilities or improper public behavior.

- People endangered when swimming at unauthorized areas.

- Safety risks at waterfalls.

- Deterioration and vandalism of historic buildings.

- Noise interfering with enjoyment of nature.

None of these are completely unexpected, and some can be managed, although not adequately at current visitor levels and funding and staffing levels. All of which points to the question of promoting additional visitors through a name change. Some have observed that there are even people who visit “national parks,” with their campers clogging the roads just so they can check another off their list.

To the NPS’s credit, the $21 million it has been awarded from the Great America Outdoors Act to rebuild some 14 miles of Route 209, a major thoroughfare running through the Pennsylvania side of the area, may allow future regular funds to be used for other purposes, and it plans to pursue additional funding from that source. It expects to be able to improve two sections of the Old Mine Road on the NJ side in the next year too from that source. Yet in terms of total need, at best it is but a very modest start, and as future funds are awaited, wear and deterioration continue.

A Lesson from the Past as a Guide for the Future

When trying to fairly balance the competing arguments, it is instructive to look back to the position expressed by former New Jersey Governor William T. Cahill in 1972, when the idea of building a dam and the recreation area was under debate. At a meeting of the Delaware River Basin Commission, he expressed concerns over “adverse environmental and financial impact,” and said he would not support the project unless its then-planned annual visitorship of 10 million would be reduced to 4 million (near what it is today). He further demanded that the Federal government pledge to pay for the majority of the cost of the expanded highway network that would be needed, as well as expressing concern over river pollution.[20]

When trying to fairly balance the competing arguments, it is instructive to look back to the position expressed by former New Jersey Governor William T. Cahill in 1972, when the idea of building a dam and the recreation area was under debate. At a meeting of the Delaware River Basin Commission, he expressed concerns over “adverse environmental and financial impact,” and said he would not support the project unless its then-planned annual visitorship of 10 million would be reduced to 4 million (near what it is today). He further demanded that the Federal government pledge to pay for the majority of the cost of the expanded highway network that would be needed, as well as expressing concern over river pollution.[20]

Cahill concluded his statement by saying that “the arrival of large numbers of visitors would inevitably lead to intrusive and tawdry land use.” The New York Times characterized his position as being “to prevent unspoiled open areas from being trampled and wrecked by sightseers.”[21]

(Cahill’s successor, Governor Brendan T. Byrne, later was to cast the official vote that killed the dam. Looking back on the controversy years later, he noted that “nobody had thought through all of the possible effects.”[22])

A representative of New York’s governor at the DRBC meeting called Cahill’s position “statesmanlike,” and the governor of Delaware praised his “farsightedness.”[23]

What Cahill said in 1972 provides reasonable guidance for today. The Donahue/Sierra Club proposal is thin on specifics, and unconvincing as to supportive funding and how and when needs, current and resulting, will be addressed. It requires a leap of faith, at the risk of adding harm. It’s not just a matter of local hunters and residents being opposed, it’s a matter of preserving a national asset to endure into the future.

The opposition, reflecting a variety of concerns, has faced the challenging task of addressing a seemingly wonderful proposal that is couched in broad, high-level aspirations, tailored to attain approval from the top down, rather than to assure enduring success. In short, it’s hard to embrace a proposal that lacks a detailed or assured plan, either economic, ecological, or historical. To encourage more visitors to a stressed park would be placing the proverbial cart before the horse.

The river, the adjacent agricultural lands, the mountains and lakes, the trails, and the wondrous expressions of nature are too important to be hit with yet another thinly conceived idea dropped from above. A neglected aspect of all of this is the lack of any overall planning that would take into account the substantial number of other Federal, state, and local park facilities in the metropolitan region.

There is nothing simple about what to do. There are multiple perspectives and values that require balancing. National parks, by whatever name, are both a treasure and a challenge. They need to be preserved for the future as well as being enjoyed today.

To date, the proposal to create a park and preserve does not appear to have achieved anything constructive. It has inflamed emotions, and diverted energies that might better be devoted to addressing the Recreation Area’s current critical needs.

What IS needed, is concerted action to obtain additional Federal funds to catch up on the site’s existing infrastructure backlog and service needs, and to pursue this through open and constructive dialog that respects the perspectives of all parties. And only then to focus on the name of this wonderful treasure.

So for now and very likely for the future, it is more than reasonable to conclude:

See Our Full Tocks Island / Recreation Area History

The Proposal for the dam. The battle against it.

The effect of Eminent Domain. The loss of communities. And more…

___________________

Sources

These thoughts reflect some years of pondering and writing about the Delaware Water Gap Recreation Area,[25] an area of great natural wonder and major challenges. Its existence is in some ways almost an accident. Specific additional sources for this paper are listed below.

[1] Richard C. Albert, Damming the Delaware (University Park: Penn State University Press, 1987).

[2] See https://jimquest.com/writ-history-tocks-domain/

[3] As one example, an email to the author dated August 25, 2021 from staff at the DEWA NPS notes that “After we pay for staff, we have between 1.5 and 2 million to do everything else in the park, including purchasing things like asphalt, road salt, printer paper, vehicle maintenance and parts, toilet paper, cleaning supplies, and so on and so on.”

[4] As one example, see extended comments by Robert Flatt regarding visitor count methodologies, at https://www.facebook.com/groups/nonationalpark. To be sure, the multiple roads and trails present a difficult measuring situation at best, which the Park Service endeavors to manage by statistical methods, often in the face of difficult field conditions.

[5] As cited on the Friends of the Old Mine Road Facebook page on August 9, 2022, and on the DEWA Facebook page (images combined).

[6] Sources include Delaware Water Gap Redesignation Project: A Project of the Pennsylvania and New Jersey Chapters” (see https://www.sierraclub.org/new-jersey) and “Debunking myths about Delaware Water Gap getting a national park designation” (see https://www.lehighvalleylive.com/opinion/2022/03/debunking-myths-about-delaware-water-gap-getting-a-national-park-designation-opinion.html).

[7] Jason Nark, “Residents fight back against proposed national park at the Delaware Water Gap,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 2, 2022. https://www.inquirer.com/news/pennsylvania/national-park-river-delaware-gap-delaware-fishing-hunting-20220808.html.

[8] Created by Caitlin Black.

[9] For the complexity of who speaks for the Lenape heritage, see “Park Prophets” at https://www.spotlightpa.org/newsletters/palocal/jul-15-thorny-push-for-pennsylvanias-first-national-park/. Also see Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/groups/632055634520469/user/1114512640 for concerns of the Turtle Clan, Lenape Nation, which expresses support of the No National Park effort.

[10] Meeting with Park Service Director Charles F. Sams (center) by PA Sierra Club official Jacqline Wolf Tice (l) and John Donahue, July 12, 2022.

[11] Ibid.

[12] https://amp.theguardian.com/environment/2021/may/12/new-river-gorge-newest-national-park-west-virginia?fbclid=IwAR04-zWijgVhEcwd94r2fqenOiQ8p_8LdpFhfbsbr0KUkvSoHeOnjahWqPo. Local official’s comment cited by Hull on Facebook page and in email to author dated August 23, 2022.

[13] See list at https://www.nonationalpark.org/post/current-counties-municipalities-opposed-to-the-re-designation-of-the-dwgnra-to-a-national-park.

[14] https://delawarecurrents.org/2022/06/30/both-sides-on-delaware-river-national-park-plan-dig-in/.

[15] Comment and photo by James Kaval, Friends of the Old Mine Road Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/groups/1293431177377560, August 16, 2022. Also see similar negative comments about the proposed park on that Facebook page.

[16] “National Parks are booming. That may ruin your next trip,” by Greg Iacurci. August 22, 2021. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/08/22/national-parks-are-booming-that-may-ruin-your-next-trip.html?fbclid=IwAR3L9WzqQUT4uL8Wp3-KP5T5EyemHbg1XyCwmdsNeOdNNpmj5gBo_ZuFOLY. Also see https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/nov/20/national-parks-america-overcrowding-crisis-tourism-visitation-solutions.

[17] News Release, “National Parks hosted 237 million visitors in 2020.” https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1207/02-25-21-national-parks-hosted-237-million-visitors-in-2020.htm

[18] Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, Visitor Use Management Plan. National Park Service, November 2020. Available at https://www.nps.gov/dewa/getinvolved/upload/DEWA-Final-VUM-Plan_December2020.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1QzIG5TQuPOeXPL3FIO2VQ2XIySqAgnJY4cZTteL-OfHHICmAAfzLZzIs

[19] Composite of photos from Visitor Use Management Plan, Ibid.

[20] Ronald Sullivan, “Cahill Withholds Tocks Is. Support Demands Change,” New York Times, September 14, 1972.

[21] Sullivan, “Cahill Wins Support on Plan to Reduce Tocks Island Project,” New York Times, October 3, 1972.

[22] Duca-Sandberg, Kathleen, “The History of the Tocks Island Dam Project: Environmental War or the War in Vietnam,” Master’s Thesis, Seton Hall University, 2011, p. 77.

[23] Sullivan, “Cahill Wins Support …”.

[24] Retrieved and edited from https://delawarecurrents.org/2022/06/30/both-sides-on-delaware-river-national-park-plan-dig-in/

[25] See https://jimquest.com/writ-history-tocks-island/ and related pages linked therein.

[10]

[10]